The European Union-funded HEARTS project has successfully completed a second, expanded radiation testing campaign at its CERN facility.

Over the course of two weeks in November and December 2025, 16 companies and research institutes spent over 200 irradiation hours at CERN testing electronic components and devices for use in space and for high-energy physics applications.

The HEARTS (High-Energy Accelerators for Radiation Testing and Shielding) project is aiming to establish two new European radiation testing facilities for space applications, one at CERN and the other at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany.

The two facilities are unique in Europe in being able to offer very-high energy, heavy ion electronics testing, meaning teams can see how their electronics hold up against particularly strong and penetrative radiation that they could be exposed to in space.

This is the second industrial user pilot campaign at CERN, with a significantly increased number of users following the 2024 run that welcomed 10 companies and research institutes.

In total, six of the 16 users participating in the 2025 run paid for access, while the rest either received beamtime hours through their association with the project or by applying through the RADNEXT project, which offers transnational access to radiation facilities in Europe.

CERN facility is ‘important’ for Europe’s radiation effects testing infrastructure

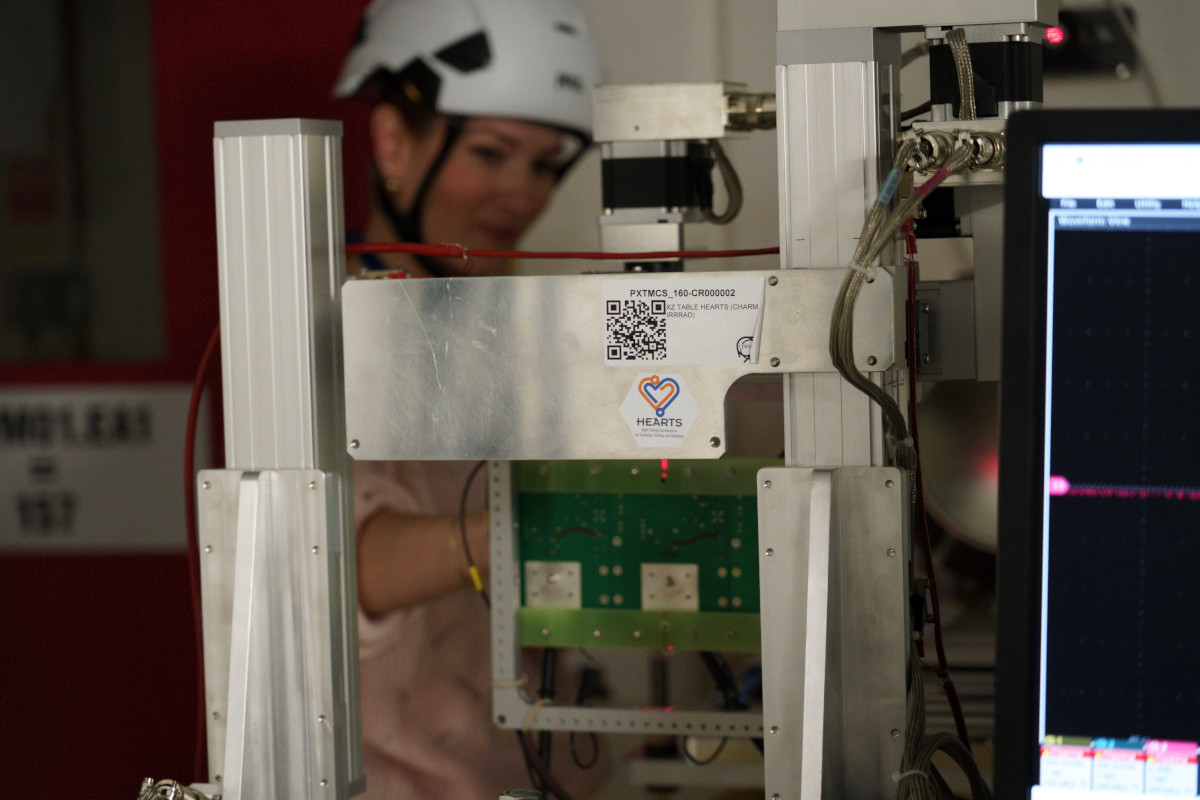

The HEARTS@CERN facility is located at CERN’s IRRAD facility. Every year for a period of a few weeks, CERN injects the Large Hadron Collider with heavy, lead ions. The HEARTS project takes advantage of this period to use the lead ions for radiation effects testing.

One of the main goals of the project is to provide companies with more options to test devices with very high energy, heavy ions. This need is increasing as the architecture of chips gets more complex. Today, chips used for space applications tend to have more sensitive areas that are closer together and could be damaged by a single penetrative particle. Further to this, “delidding” chips – meaning removing the protective packaging around them – is becoming harder and there is more chance of damaging the chip (or die) inside. With the HEARTS facilities, chips can be tested without the need to delid.

“The fact that we can do these complex tests, and this facility supports that whilst others wouldn’t, it opens up an array of possibilities for us,”

said Wouter Benoot, co-founder and CTO of Belgian start-up EDGX that tested at CERN for this first time.

EDGX specialises in building technologies that allow computing as a service to take place in space, with the company currently focusing on computers tailored towards satellites. During this campaign at CERN, they tested various off-the-shelf solid state drive (SSD) memory storage devices. The team prepared boards of eight SSDs from different vendors all with different properties, looking for weak spots and trying to determine the destructive threshold of each device.

Benoot said he was glad they were able to get a slot at the CERN facility as they were able to run tests that they could not do easily elsewhere.

“We can test these complex devices at very high LETs. They have multiple chips that all have different stack ups, all with different depths, so in a regular facility you can maybe take one chip at a time and it would be very tedious,” he said.

“If you want to do eight SSDs in one go, you have to have very high energies. We also tested double-sided drives, which we couldn’t have done at another facility.”

Tyvak International is another company that tested at the HEARTS@CERN facility for the first time during the 2025 campaign. The satellite specialist is leading a consortium of partners building a CubeSat called Ramses CubeSat 1 (RCS-1) that will investigate the Apophis asteroid during its close approach to Earth in 2029.

The Tyvak team tested critical components of printed circuit boards (PCBs) at CERN, which will be used in the design of RCS-1.

Federico Parigi, program management area manager at Tyvak International, said they chose to test at CERN because it was

“the best facility we could find in Europe in terms of the completeness of the tests we could perform, accommodation, and scheduling requirements”.

For Parigi, having the HEARTS@CERN facility as an option in Europe is vital to the space industry.

“Not every program we work on needs tests carried out in such facilities, but we do have some programs that do. Given that there are just a handful of available facilities in Europe, it’s extremely important for us to have facilities such as HEARTS@CERN relatively close to home,” he said.

Seibersdorf Laboratories consult with the HEARTS team during their test campaign (Credit: Gerd Datzmann).

Seibersdorf Laboratories was another user during the 2025 campaign. The company was set up in 2008 to support the commercialisation of technologies coming out of the Austrian Institute of Technology. One of its core specialities is radiation safety of electronics, managed by its Aerospace Radiation Competence Centre.

The team used the HEARTS@CERN facility to run radiation shielding tests on behalf of their client, the US-based company Cosmic Shielding Corporation.

“We used the CERN campaign to investigate the performance of a shielding development from Cosmic Shielding Corporation, by comparing the company’s proprietary product with aluminium,”

said Christoph Tscherne, head of Seibersdorf Laboratories’ Aerospace Radiation Competence Centre.

“We measured the single event transients of commercial operation amplifiers behind different shielding configurations.”

Tscherne said that working with the HEARTS and CERN technical staff went “flawlessly”.

“They really went out of their way to help us, even at one point taking their own cars to help us transport our equipment from storage to the facility,” he said.

Reflecting on the broader importance of the infrastructure, Tscherne emphasised the growing relevance of HEARTS@CERN for the European space community.

“In the [space] community, there will always be a need, to some extent, for high-energy beams,” he said. “HEARTS@CERN will not replace existing facilities, but it is an important and much-needed addition.”

The HEARTS@CERN facility will host one user run in the summer of 2026 before a short break in 2027 as CERN’s accelerator complex shuts down for maintenance. Calls for industry and scientific users for the 2026 campaign will be announced on the project website in the coming weeks.

See also

- Applications for commercial beam time at HEARTS@CERN in November-December 2025 is now open!

- PhD opportunity in Applied Physics – Space Radiation Effects at CERN

- EU project to boost Europe’s space radiation testing capabilities marks significant milestone

- CERN Heavy Ion Run

- How to make CERN and GSI dosimetry comparable?